- NASA unveiled the deepest, sharpest infrared image of the distant universe ever captured on Tuesday.

- Various estimates suggest Earth-like planets that could harbor life are abundant in the universe.

- The James Webb Space Telescope's instruments capture distant galaxies, stars, and worlds in unprecedented detail.

It's easy to lose yourself in the James Webb Space Telescope's first image. Snail-spiral galaxies, gleaming stars, and minuscule red dots surely represent billions of unknown worlds.

"The deep field image fills me with wonder and hope," Lisa Kaltenegger, professor of astronomy at Cornell University and director of the Carl Sagan Institute, told Insider.

Webb's image of the distant universe covers an area of the sky that you can blot out by holding a grain of sand at arm's length. Still, it contains thousands of galaxies, according to Kaltenegger, along with the possibility of billions of Earth-like planets. So far, the hunt for signs of life beyond Earth has turned up empty.

But astronomers say there are likely an abundance of places where life might thrive. Looking at Webb's pictures, it's hard to believe otherwise.

An abundance of distant worlds

There are up to 400 billion stars teeming with planets in the Milky Way alone. We don't know for sure, but scientists have tried to calculate how many Earth-like planets are orbiting all those stars. Their estimates range from 300 million to 10 billion potentially habitable worlds.

Outside that, there are about 100 billion to 200 billion galaxies in the universe, each one home to 100 million stars, on average, and at least that number of planets.

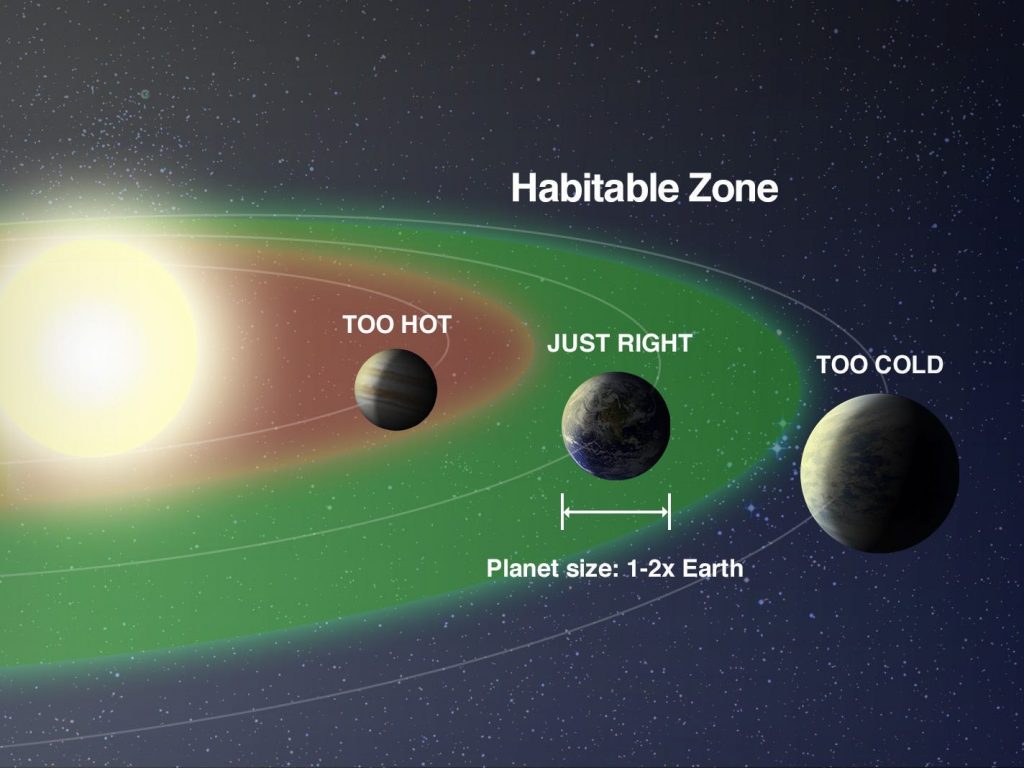

Astronomers have already captured direct evidence of 5,000 planets beyond our solar system, according to NASA's Exoplanet Archive. Hundreds of these worlds sit in the "Goldilocks Zone," the orbital range around a star where the temperature is just right — not too hot and not too cold — for liquid water to exist on the planet.

Observations by NASA's Kepler mission suggest that one out of every five stars has a planet orbiting it within this just-right distance, according to Kaltenegger. "I like our chances of finding other Earth-like planets, and hopefully other Earth-like planets that also host life," Kaltenegger said.

The possibilities for life aren't limited to planets. Some ocean moons within our solar system are leading candidates for alien life. There's Jupiter's icy moon Europa, and Saturn's moon Enceladus, which have oceans of liquid water deep beneath their ice crusts. Astronomers think there's a chance life could thrive there. Surely, there are other Europas and Enceladuses in other star systems.

Still, despite the myriad galaxies and worlds already imaged and studied, astronomers are unsure about the odds of life arising elsewhere.

"We don't know how easy or hard it is to make life — that is why the search is so exciting," Kaltenegger said, adding, "Right now, I'd say the chances are between zero and 100%, but I am hopeful it won't be zero."

Looking for life as we know it

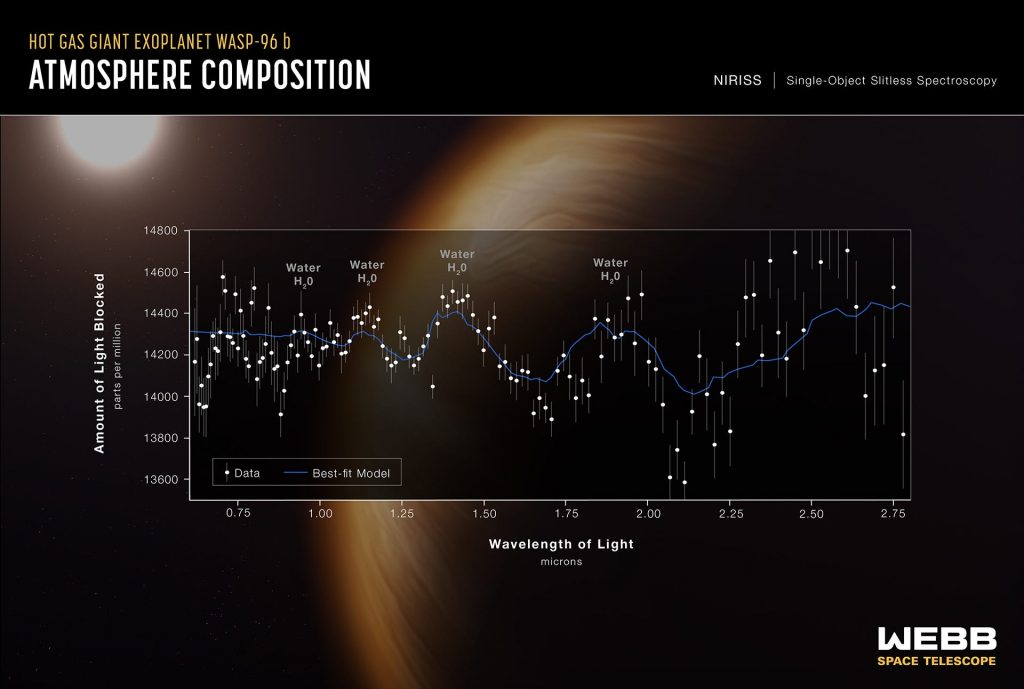

To understand whether exoplanets, or planets around other stars, have the conditions to host life, researchers measure the chemical makeup of their atmospheres. They do this by looking at how starlight gets filtered by the atmosphere, which dips at very specific wavelengths that correspond to different molecules.

Astronomers typically look for the ingredients that sustain earthly life — liquid water, a continuous source of energy, carbon, and other elements — when hunting for life in distant worlds. For instance, detecting methane in an exoplanet's atmosphere could be an indication of biology. According to Kaltenegger, these building blocks of life appear to be abundant in our solar system and the universe.

What's more, a potential alien astronomer looking for life beyond their planet might pick up on signs of life from Earth in a similar way. In 2021, Kaltenegger co-authored a study that found that more than 2,000 stars, some with their own planets, have a front-row seat to look toward the Earth as it passes around our sun. "That's just within 300 light-years, in our cosmic front yard, in terms of distance," Kaltenegger said.

One limitation in scouring the cosmos for alien life is that scientists' definition of what a life-supporting planet might look like is based on what we know about life on Earth. But by discovering and studying new worlds, astronomers can hone in on what makes a world habitable beyond a sample size of one — Earth.

Leveraging Webb's power to study other worlds

Since the first world outside our solar system was confirmed in 1995, astronomers have searched for other planets orbiting sun-like stars. Because these worlds are so far away, space-based telescopes like the Hubble Space Telescope have dramatically enhanced their planet-hunting capabilities, and the James Webb Space Telescope makes more such discoveries almost inevitable.

Webb will allow for unprecedented views into these distant planets. "With the James Webb Space Telescope, we can explore the chemical makeup of the atmosphere of other worlds — and if there are signs in it that we can only explain by life," Kaltenegger said.

There are 70 planets scheduled for study in Webb's first year alone. Already, Webb captured the signature of water, along with previously undetected evidence of clouds and haze, in the atmosphere of WASP-96 b — a giant and hot gas planet that orbits a distant star like our sun.

"While the Hubble Space Telescope has analyzed numerous exoplanet atmospheres over the past two decades, capturing the first clear detection of water in 2013, Webb's immediate and more detailed observation marks a giant leap forward in the quest to characterize potentially habitable planets beyond Earth," NASA said.

Kaltenegger is part of a team that will dedicate 200 hours of Webb's telescope time in its first year to study faraway places, including worlds circling Trappist-1 — a cool, dim star 40 light-years from Earth.

"It is an amazing time in our exploration of the cosmos," Kaltenegger said, adding, "Are we alone? This amazing space telescope is the first-ever tool that collects enough light for us to start figuring this fundamental question out."